CS224W-Machine Learning with Graph-Fast Neural Subgraph

Subgraphs and Motifs

Definition:

- Given graph :

- Def 1. Node-induced subgraph: Take subset of the nodes and all edges induced by the nodes:

- is a node induced subgraph iff

-

-

- is the subgraph of induced by

Alternate terminology: “induced subgraph”

- is a node induced subgraph iff

- Def 2. Edge-induced subgraph: Take subset of the edges and all corresponding nodes

- is an edge induced subgraph iff

-

-

Alternate terminology: “non-induced subgraph” or just “subgraph”

- is an edge induced subgraph iff

- Def 1. Node-induced subgraph: Take subset of the nodes and all edges induced by the nodes:

The best definition depends on the domain!

- Example:

- Chemistry: Node-induced (functional groups)

- Knowledge graphs: Often edge-induced (focus is on edges representing logical relations)

The preceding definitions define subgraphs when and , i.e. nodes and edges are taken from the original graph .

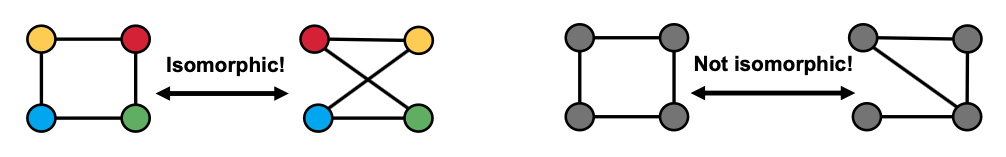

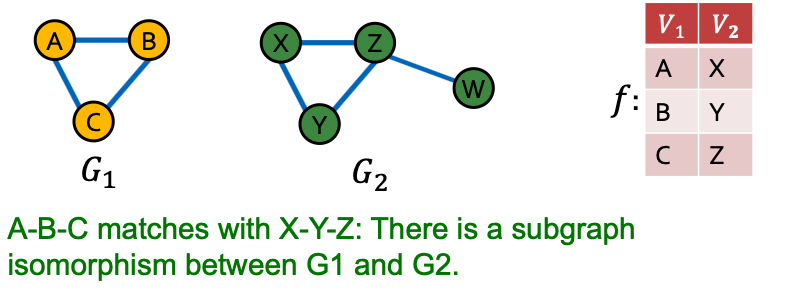

Graph Isomorphism

Graph isomorphism problem: Check whether two graphs are identical:

We do not know if graph isomorphism is NP-hard, nor is any polynomial algorithm found for solving graph isomorphism.

- is subgraph-isomorphic to if some subgraph of is isomorphic to

- We also commonly say is a subgraph of

- We can use either the node-induced or edge-induced definition of subgraph

- This problem is NP-hard

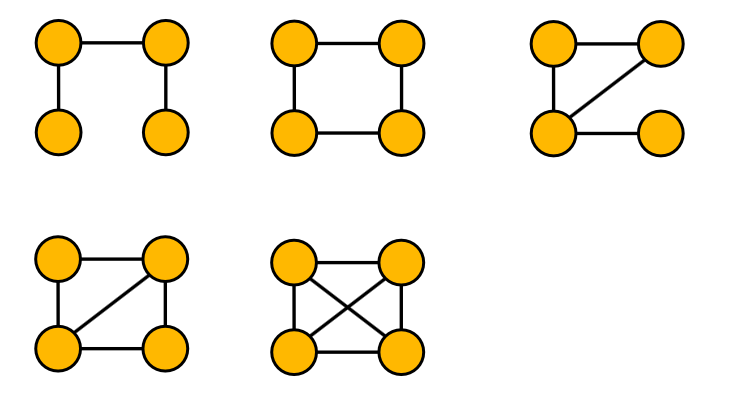

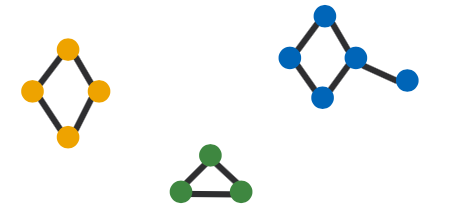

- Case Example of Subgraphs

- All non-isomorphic, connected, undirected graphs of size 4

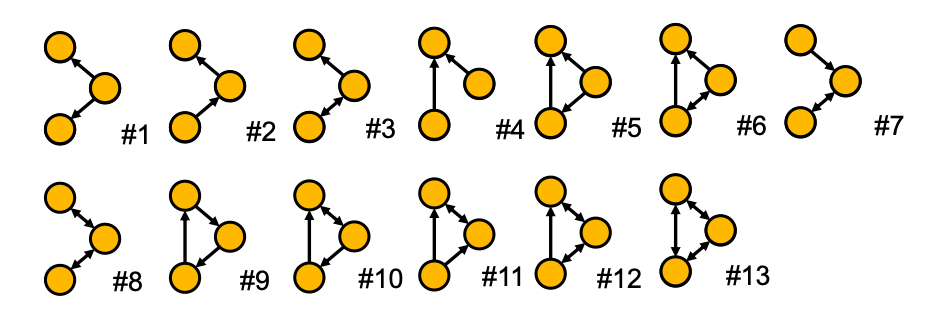

- All non-isomorphic, connected, directed graphs of size 3

Network Motifs

- Network motifs: “recurring, significant patterns of interconnections”

- How to define a network motif:

- Pattern: Small (node-induced) subgraph

- Recurring: Found many times, i.e., with high frequency. How to define frequency?

- Significant: More frequent than expected, i.e., in

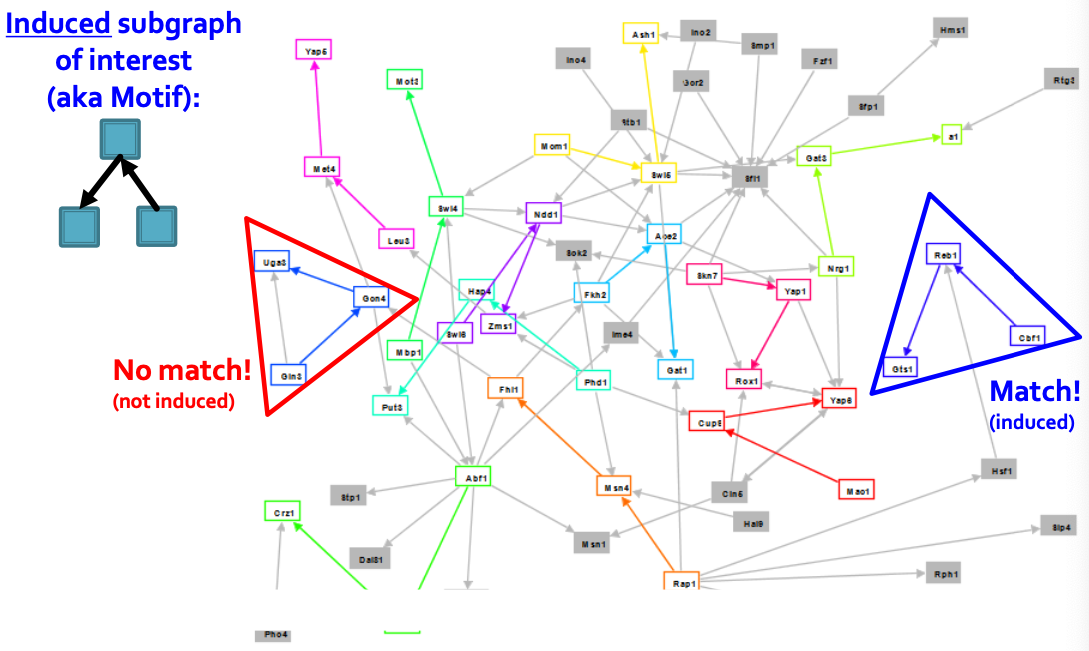

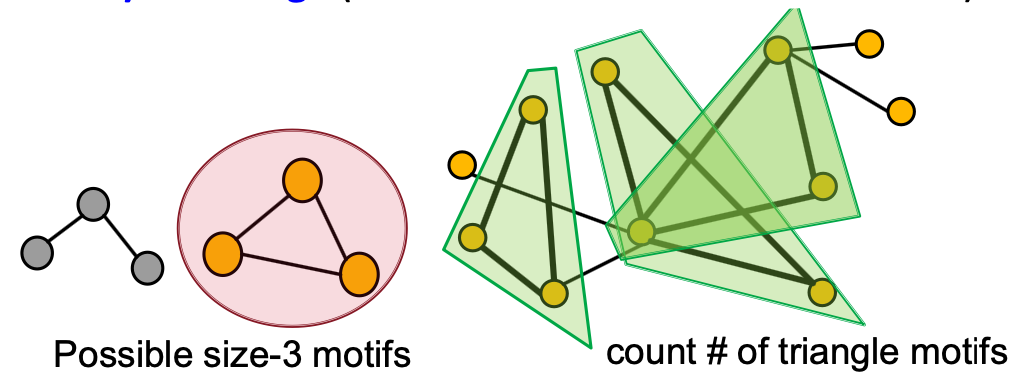

Motifs: Induced Subgraphs

the red region has 3 edges.

Why do we need motifs?

- Motifs:

- Help us understand how graphs work

- Help us make predictions based on presence or lack of presence in a graph dataset.

- Example:

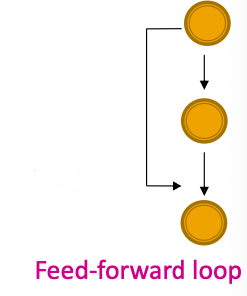

- Feed-forward loops: Found in networks of neurons, where they neutralize “biological noise”

- Parallel loops: Found in food webs

- Single-input modules: Found in gene control networks

Subgraphs Frequency

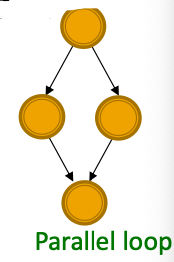

- Let be a small graph and be a target graph dataset.

- Graph-level Subgraph Frequency Definition

Frequency of in : number of unique subsets of nodes of for which the subgraph of induced by the nodes is isomorphic to

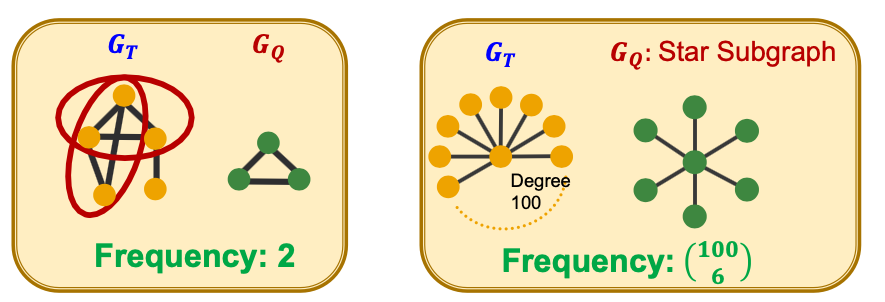

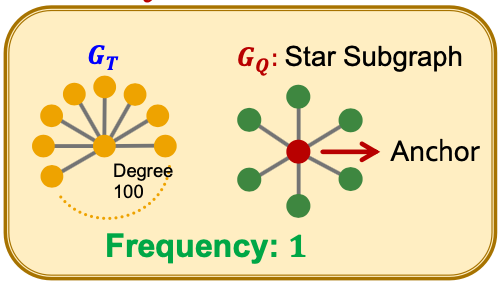

- Let be a small graph, be a node in (the “anchor”) and be a target graph dataset.

- Node-level Subgraph Frequency Definition: The number of nodes in for which some subgraph of is isomorphic to and the isomorphism maps node to .

- Let be called a node-anchored subgraph

- Robust to outliers

What if the dataset contains multiple graphs, and we want to compute frequency of subgraphs in the dataset?

- Solution: Treat the dataset as a giant graph with disconnected components corresponding to individual graphs.

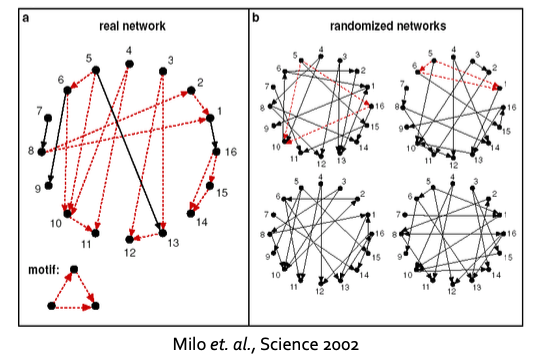

Defining Motif Significance

- To define significance, we need to have a null-model (i.e., point of comparison).

- Key idea: Subgraphs that occur in a real net work much more often than in a random network have functional significance.

Defining Random Graphs

Erdos-Renyi (ER) random graphs:

- : undirected graph on nodes where each edge appears i.i.d with probability

- How to generate the graph: Create nodes, for each pair of nodes flip a biased coin with bias .

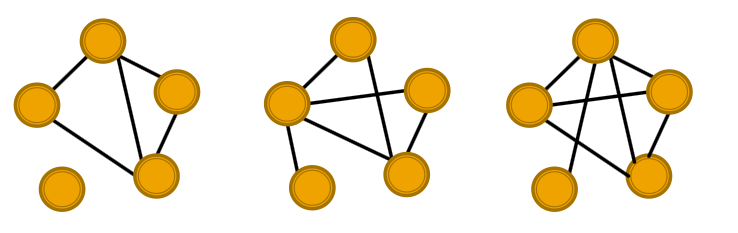

- Generated graph is a result of a random process: (Three random graphs drawn from )

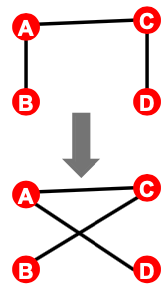

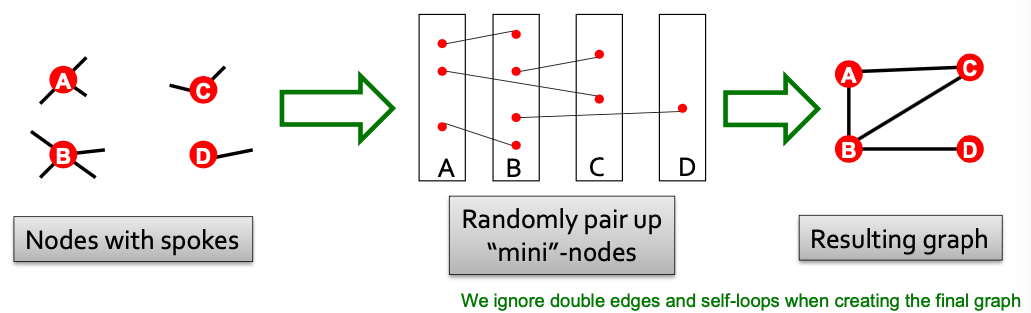

New Model: Configuration Model

- Goal: Generate a random graph with a given degree sequence

- Useful as a “null” model of networks:

- We can compare the real network and a “random” which has the same degree sequence as

- Configuration model:

Alternative for Spokes: Switching

- Start from a given graph G

- Repeat the switching step times:

- Select a pair of edges at random

- Result: A randomly rewired graph:

- Same node degrees, randomly rewired edges

- Q is chosen large enough (e.g., Q=100) for the process to converge

Motif Significance Overview

- Intuition: Motifs are overrepresented in a network when compared to random graphs:

- Step 1: Count motifs in the given graph

- Step 2: Generate random graphs with similar statistics (e.g. number of nodes, edges, degree sequence), and count motifs in the random graphs

- Step 3: Use statistical measures to evaluate how significant is each motif

- Use Z-score

Z-score for Statistical Significance

- captures statistical significance of motif :

- is # (motif ) in graph

- is average # (motif ) in random graph instances

- Network significance profile (SP):

- SP is a vector of normalized Z-scores

- The dimension depends on number of motifs considered

- SP emphasizes relative significance of subgraphs:

- Important for comparison of network of different sizes

- Generally, larger graphs display higher Z-scores.

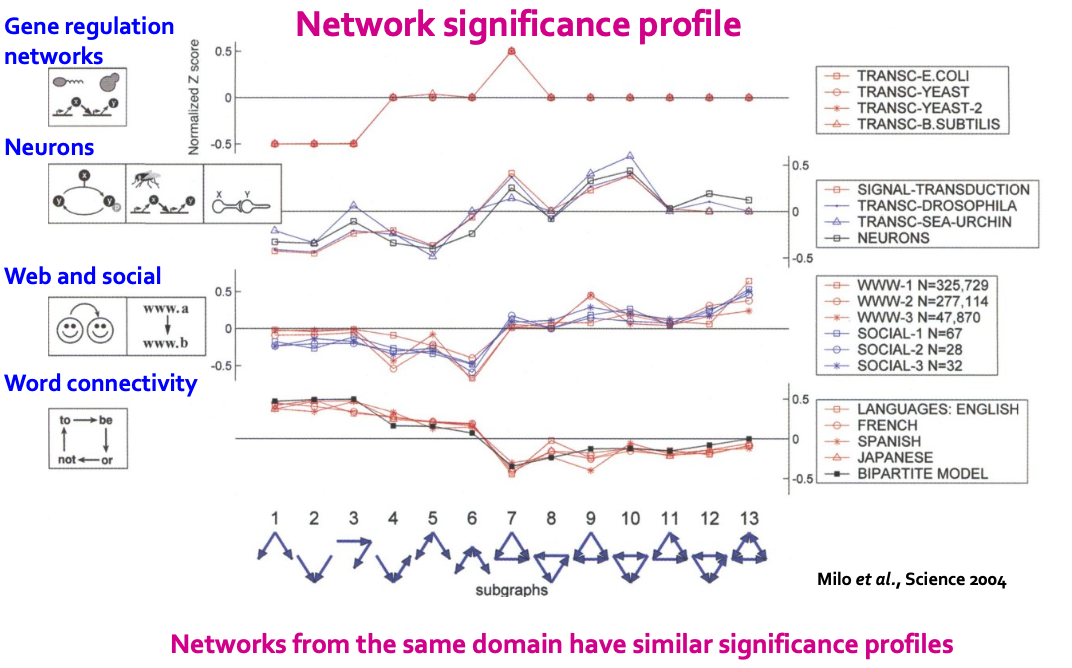

Significance Profile

- For each subgraph:

- Z-score metric is capable of classifying the subgraph “significance”:

- Negative values indicate under-representation

- Positive values indicate over-representation

- Z-score metric is capable of classifying the subgraph “significance”:

- We create a network significance profile:

- A feature vector with values for all subgraph types

- Example SP

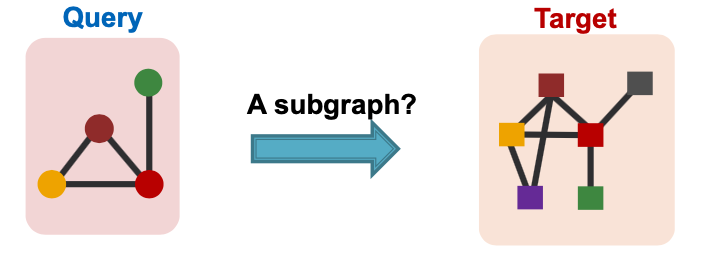

Neural Subgraph Representations

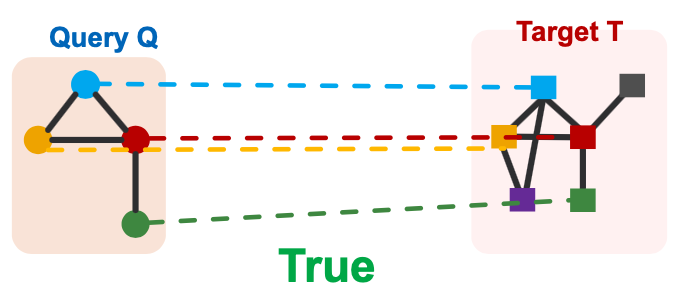

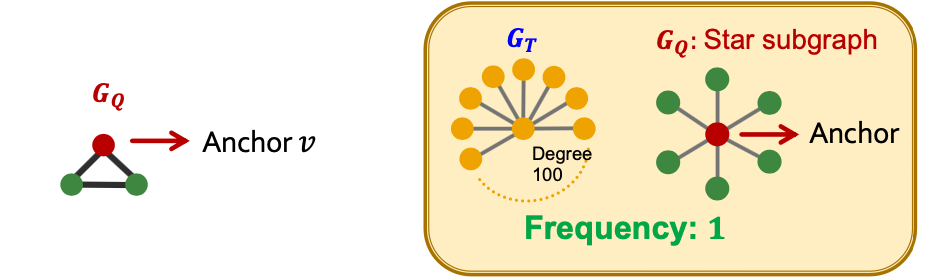

Subgraph Matching

- Given:

- Large target graph (can be disconnected)

- Query graph (connected)

- Decide:

- Is a query graph a subgraph in the target graph?

Node colors indicate the correct mapping of the nodes.

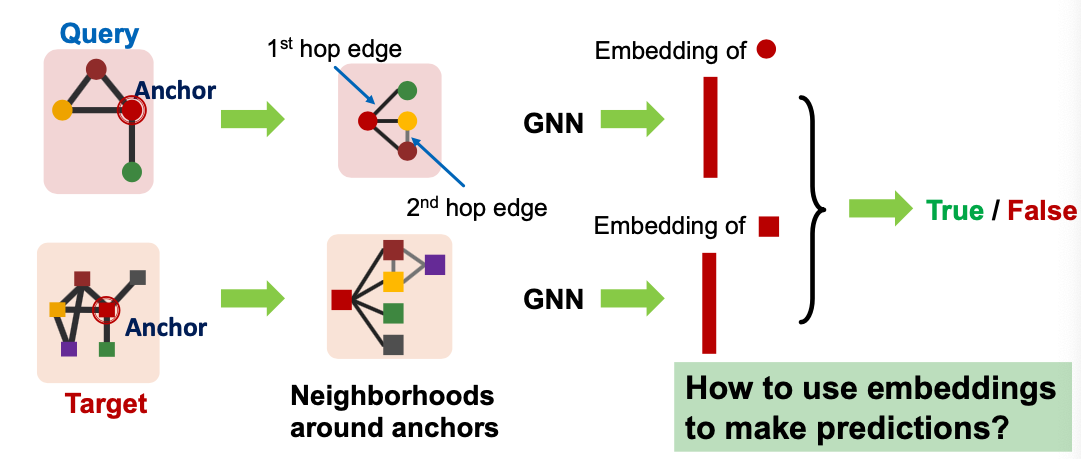

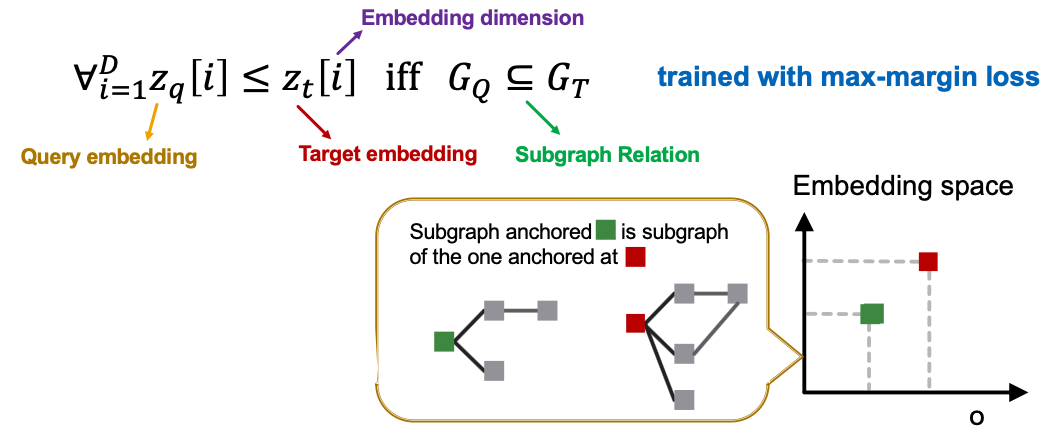

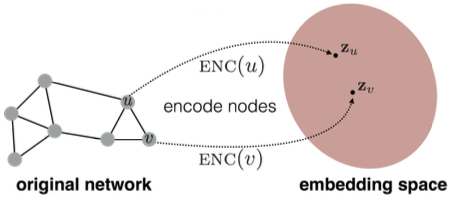

- Use GNN to predict subgraph isomorphism.

- Intuition: Exploit the geometric shape of embedding space to capture the properties of subgraph isomorphism

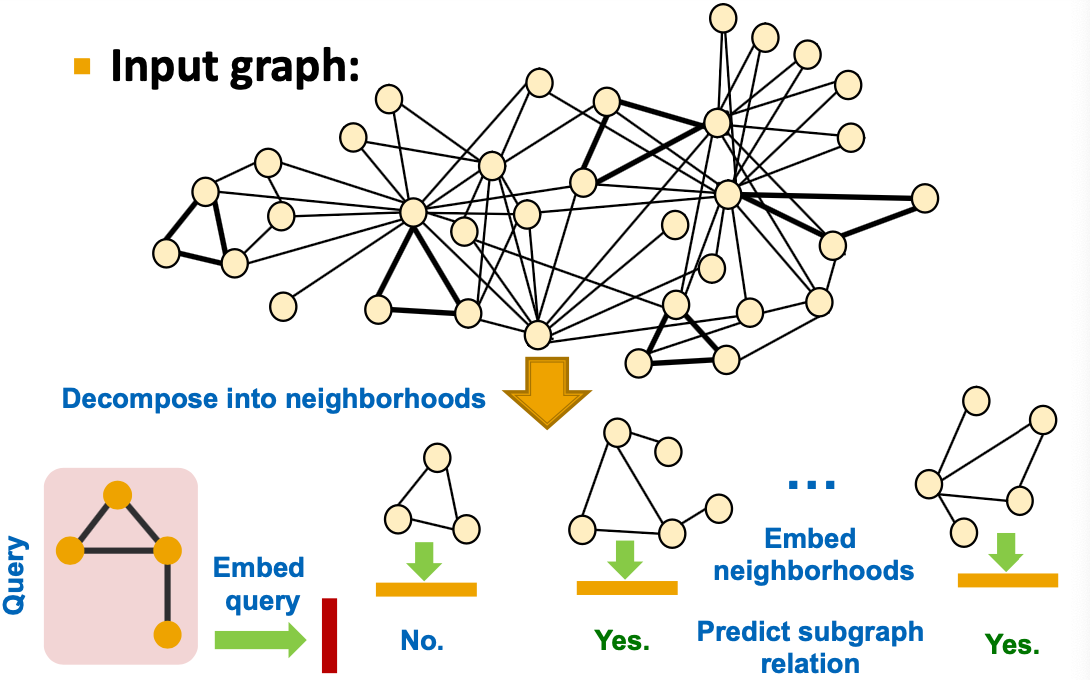

Overview of the Approach

We are going to work with node-anchored definitions:

We are going to work with node-anchored neighborhoods:

Use GNN to obtain representations of and

Predict if node ’s neighborhood is isomorphic to node neighborhood:

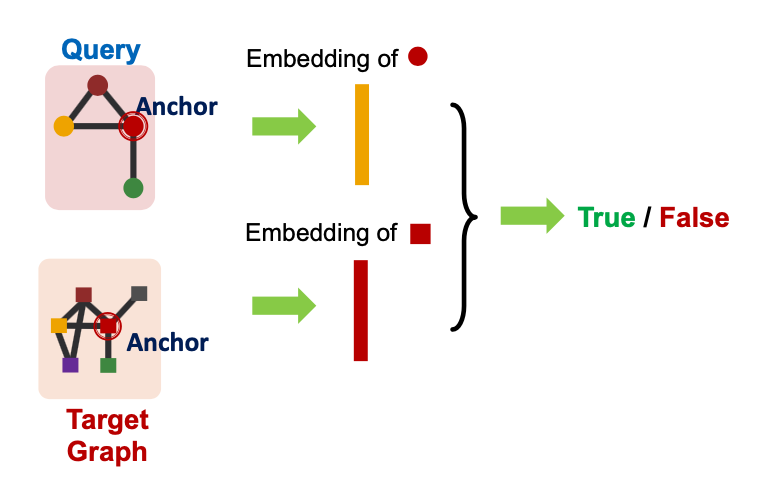

Why Anchor?

- Recall node-level frequency definition: The number of nodes in for which some subgraph of is isomorphic to and the isomorphism maps to .

- We can compute embeddings for and using GNN

- Use embeddings to decide if neighborhood of is isomorphic to subgraph of neighborhood of

- We not only predict if there exists a mapping, but also a identify corresponding nodes ( and )!

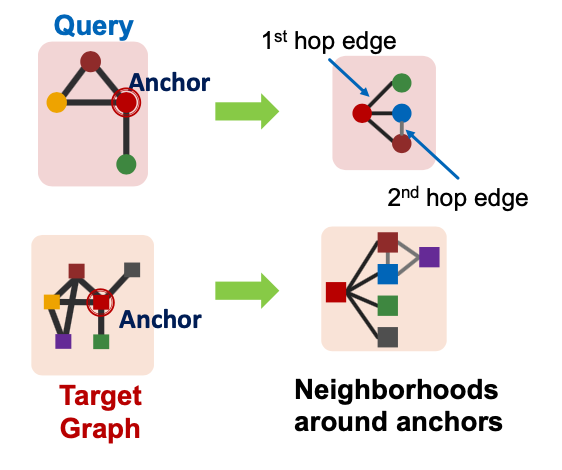

Decomposing into Neighborhoods

- For each node in :

- Obtain a k-hop neighborhood around the anchor

- Can be performed using breadth-first search (BFS)

- The depth is a hyper-parameter (e.g. 3)

- Larger depth results in more expensive model

- Same procedure applies to to obtain the neighborhoods

- We embed the neighborhoods using a GNN

- By computing the embeddings for the anchor nodes in therir respective neighborhoods.

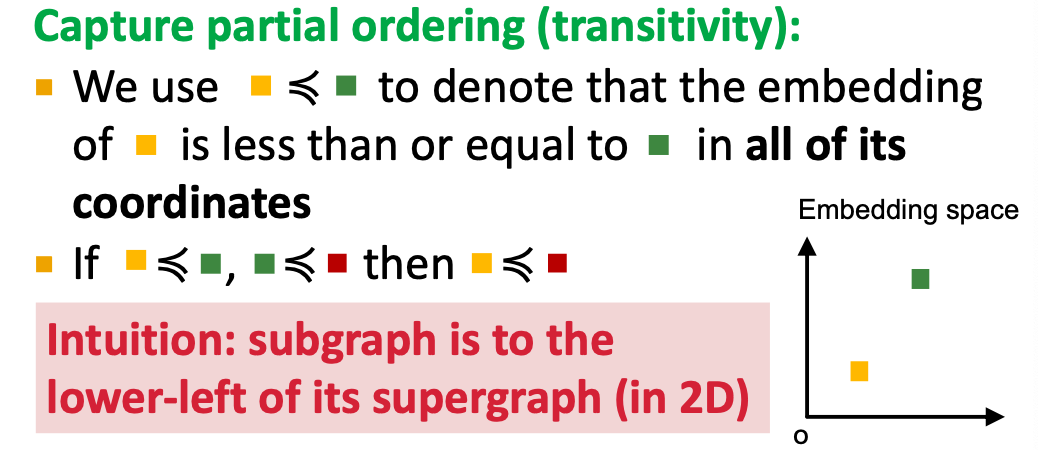

Idea: Order Embedding Space

Map graph to a point into a high-dimensional (e.g. 64-dim) embedding space, such that is non-negative in all dimensions.

Subgraph Order Embedding Space

Why Order Embedding Space?

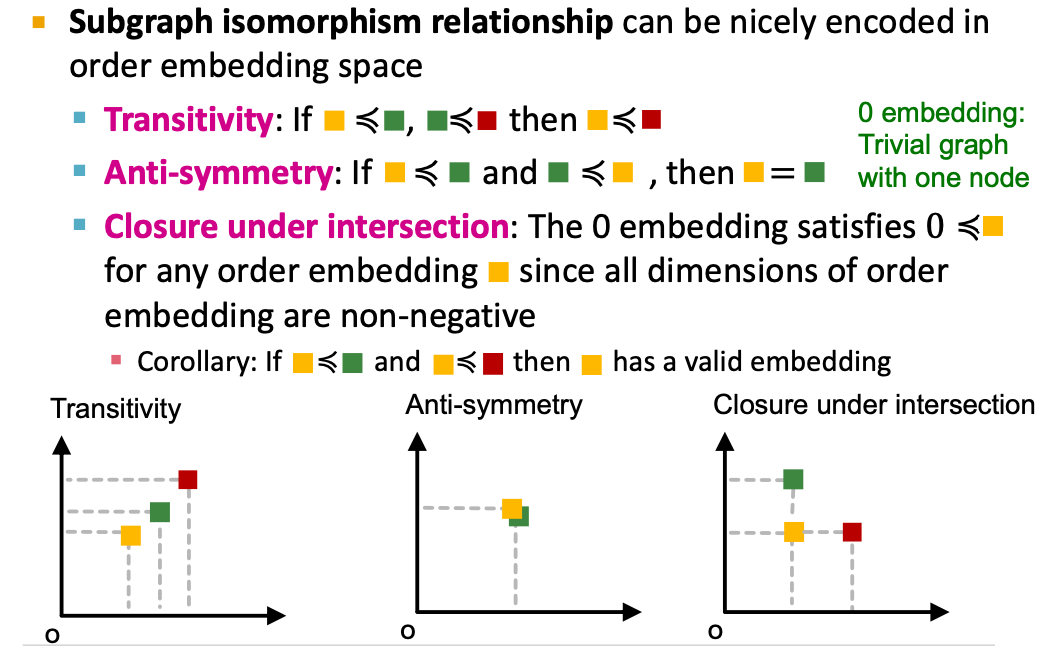

Subgraph isomorphism relationship can be nicely encoded in order embedding space

- Transitivity: If is a subgraph of , is a subgraph of , then is a subgraph of

- Anti-symmetry: If is a subgraph of , and is a subgraph of , then is isomorphic to .

- Closure under intersection: The trivial graph of 1 node is a subgraph of any graph.

- All properties have their counter-parts in the order embedding space.

- Example:

Order Constraint

- We use a GNN to learn to embed neighborhoods and preserve the order embedding structure.

- What loss function should we use, so that the learned order embedding reflects the subgraph relationship?

- We design loss functions based on the order constraint:

- Order constraint specifies the idea order embedding property that reflects subgraph relationships.

- We specify the order constraint to ensure that the subgraph properties are preserved in the order embedding space.

Order Constraint: Loss Function

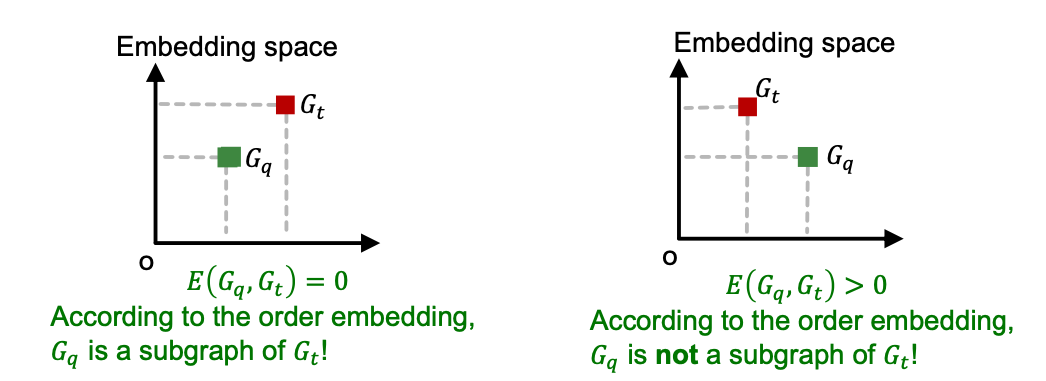

- GNN Embeddings are learned by minimizing a max-margin loss

- Define as the “margin” between graphs and

- To learn the correct order embeddings, we want to learn such that

- when is a subgraph of .

- when is not a subgraph of .

Training Neural Subgraph Matching

- To learn such embeddings, construct training examples where half the time, is a subgraph of , and the other half, it is not.

- Train on these examples by minimizing the following max-marging loss:

- For positive examples: Minimize when is a subgraph of

- For negative example: Minnimize

- Max-margin loss prevents the model from learning the degenerate strategy of moving embeddings further and further apart forever.

Training Example Construction

- Need to generate training queries and targets from the dataset

- Get by choosing a random anchor and taking all nodes in within distance from to be in .

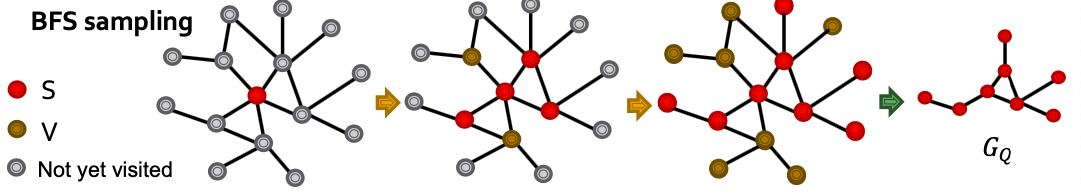

- Postive examples: Sample induced subgraph of . Use BFS sampling:

- Initialize

- Let be all neihbors of nodes in . At every step, sample of the nodes in , put them in . Put the remaining nodes of in .

- After steps, take the subgraph of induced by anchored at

- Negative examples( not subgraph of ): “corrupt” by adding/removing nodes/edges so it’s no longer a subgraph.

Details:

- How many training examples to sample?

- At every iteration, we sample new training pairs

- Benefit: Every iteration, the model sees different subgraph examples

- Improves performance and avoids overfitting - since there are exponential number of possible subgraphs to sample from.

- How deep is the BFS sampling?

- A hyper-parameter that trades off runtime and performance.

- Usually use 3-5, depending on size of the dataset.

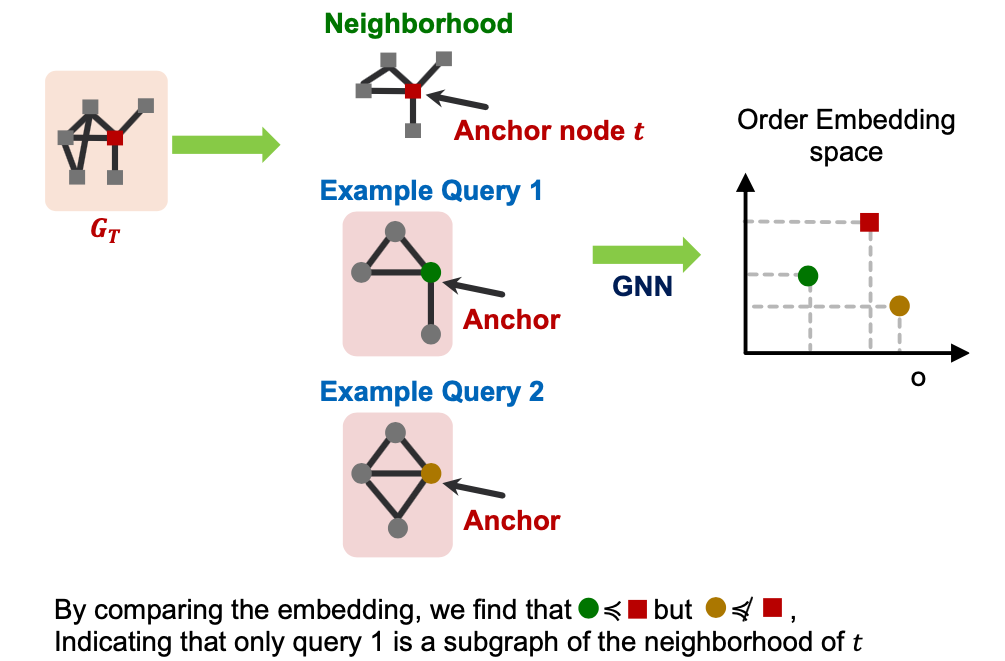

Subgraph Predictions on New Graphs

- Given: query graph anchored at node , target graph anchored at node .

- Goal: Output whether the query is a node-anchored subgraph of the target.

- Procedure:

- If , predict “True”; else “False”

- is a hyper-parameter.

- To check if is isomorphic to a subgraph of , repeat this procedure for all . Here is the neighborhood around node .

Finding Frequent Subgraphs

Generally, finding the most frequent size- motifs requires solving two challenges:

- Enumerating all size connected subgraphs

- Counting # (occurrences of each subgraph type)

- Subgraph isomorphism is NP-complete

- Feasible motif size for traditional methods is relatively small (3 to 7)

Finding frequent subgraph patterns is computationally hard

- Combinatorial explosion of number of possible patterns

- Counting subgraph frequency is NP-hard

Representation learning can tackle these challenges:

- Combinatorial explosion → Organize the search space

- Subgraph isomorphism → Prediction using GNN

Representation learning can tackle these challenges:

- Counting # (occurrences of each subgraph type)

- Solution: Use GNN to “predict” the frequency of the subgraph.

- Enumerating all size- connected subgraphs

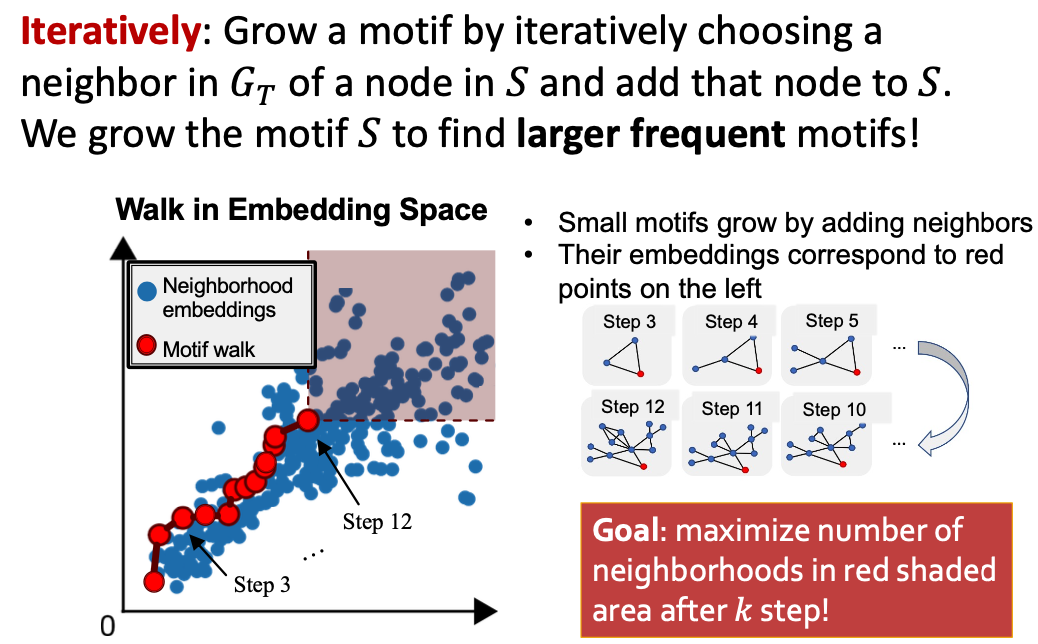

- Solution: Don’t enumerate subgraphs but construct a size- subgraph incrementally

- Note: We are only interested in high frequency subgraphs

- Solution: Don’t enumerate subgraphs but construct a size- subgraph incrementally

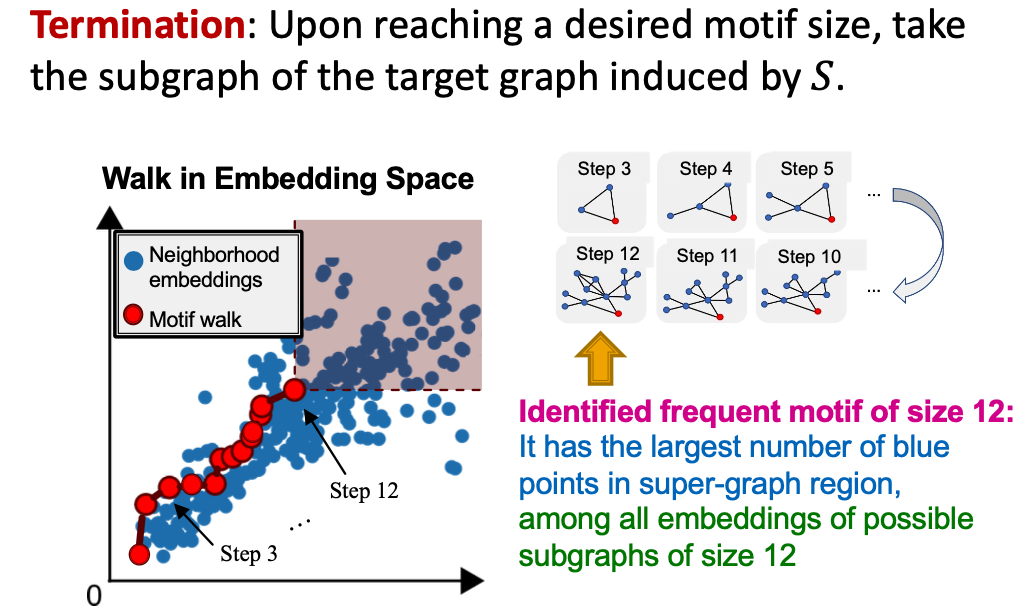

Problem Setup: Frequent Motif Mining

- Target graph (dataset) , size parameter

- Desired number of results

- Goal:: Identify, among all possible graphs of nodes, the graphs with the highest frequency in .

- We use the node-level definition: The number of nodes in for which some subgraph of is isomorphic to and the isomorphism maps to .

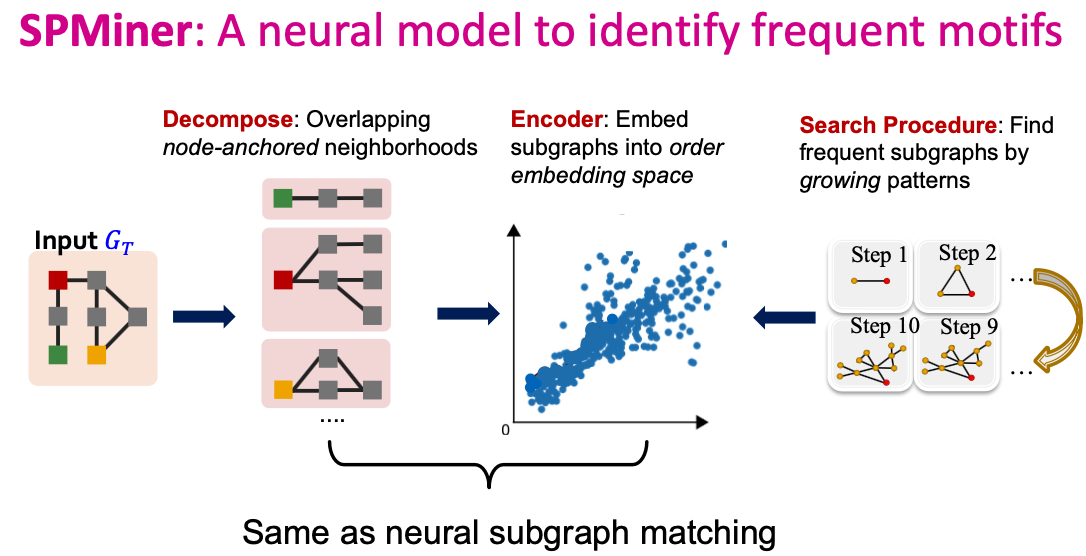

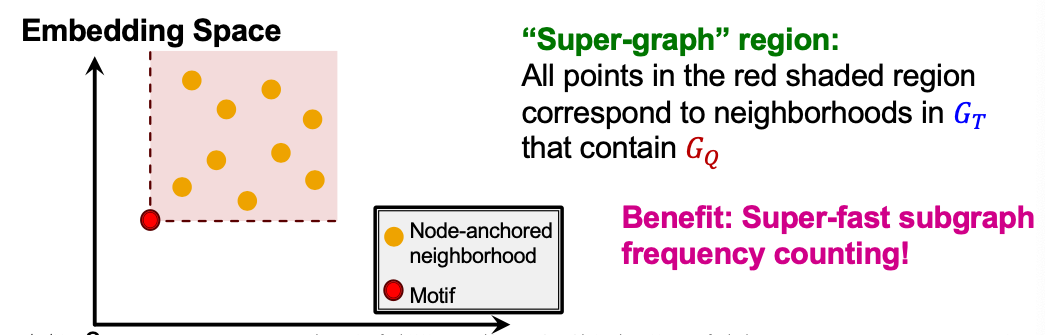

SPMiner: Key Idea

- Decompose input graph into neighborhoods

- Embed neighhborhoods into an order embedding space

- Key benefit of order embedding: We can quickly “predict” the frequency of a given subgraph

Motif Frequency Estimation

- Given: Set of subgraphs (”node-anchored neighborhoods”) of (sampled randomly)

- Key idea: Estimate frequency of by counting the number of such taht their embeddings satisfy

- This is a consequence of the order embedding space property

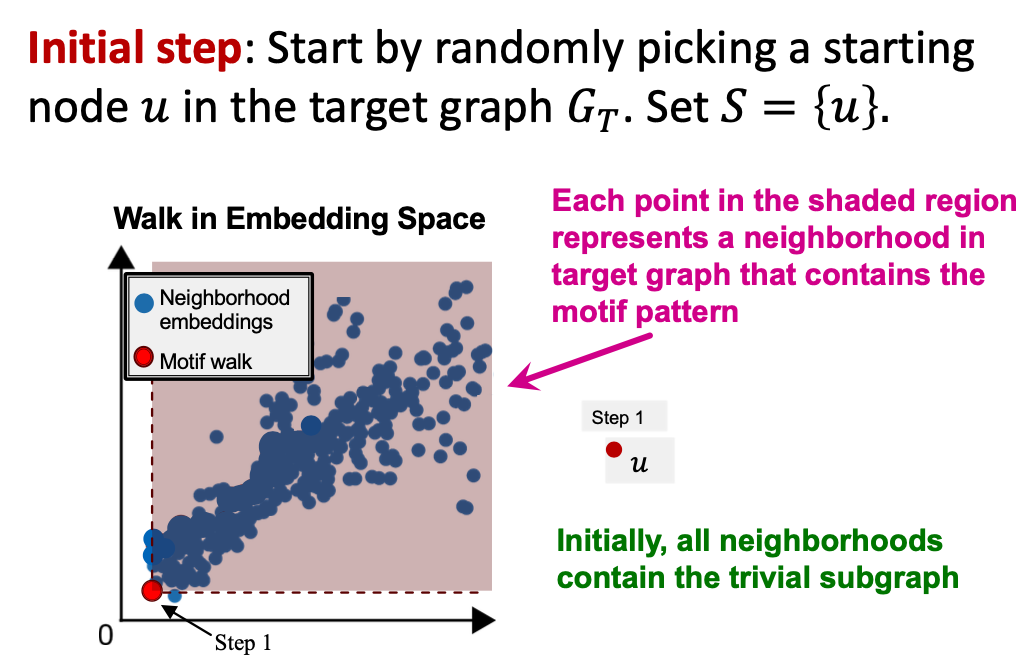

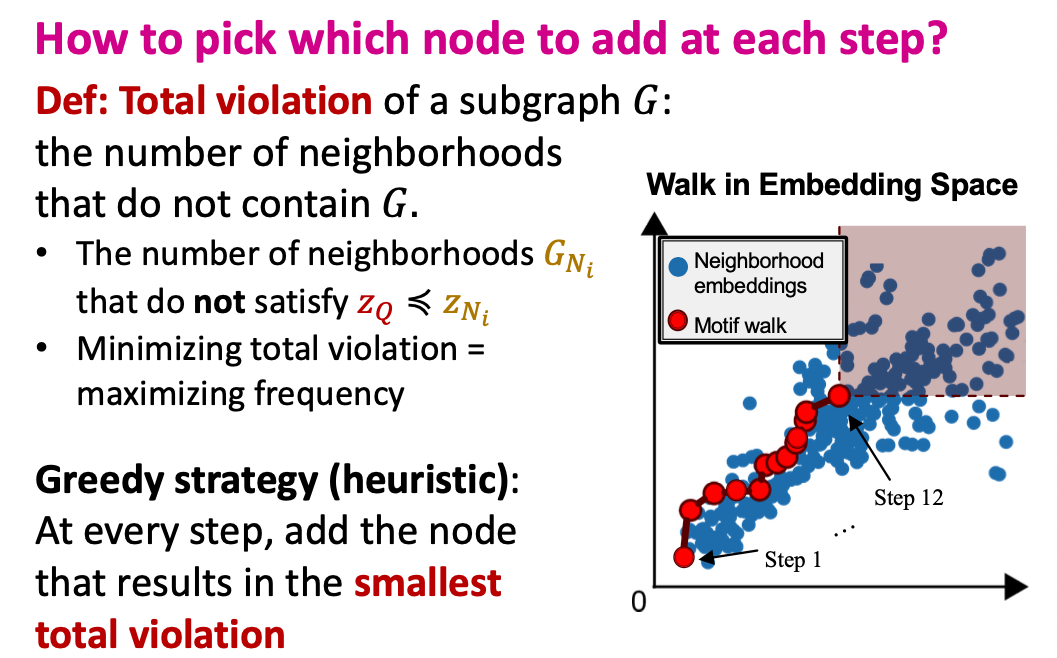

SPMiner Search Procedure

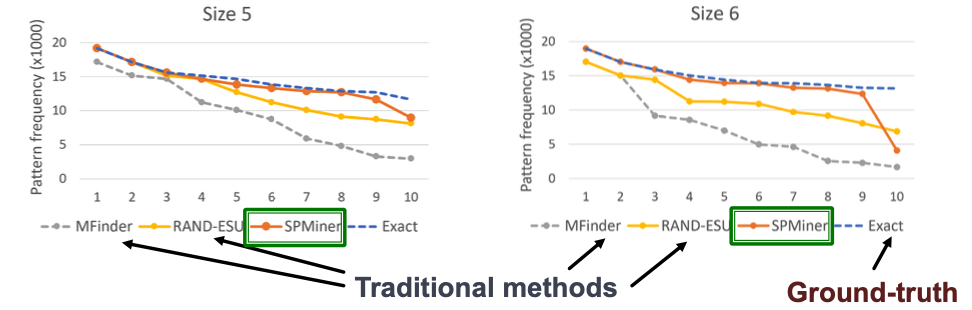

Results: Small Motifs

- Ground-truth: Find most frequent 10 motifs in dataset by brute-force exact enumeration (expensive)

- Question: Can the model identify frequent motifs?

- Result: The model identifies 9 and 8 of the top 10 motifs, respectively.